Wendi in ROP399: Learning How the Machine Learns…and Improve It!

Hi everyone! My name is Wendi Qu and I’m finishing my third year in U of T, majoring in Statistics and Molecular Genetics. I did a ROP399 research project with Dr. Pascal Tyrrell from September 2018 – April 2019 and I would love to share it with you!

his amazing experience, and it has inspired me to delve deeper into machine learning and healthcare!

Rachael Jaffe’s ROP Journey… From the Pool to the Lab!

|

| https://thevarsity.ca/2019/03/10/what-does-a-scientist-look-like/ |

and I was inclined to put my minor to the test! Little did I know that I was about to embark on a machine learning adventure.

wasn’t going to be a part of the lab for 2018-2019 year. If my background in statistics has taught me anything, nothing truly has a 100% probability. And yet, last April I found myself sitting in the department of medical imaging at my first lab meeting.

should add an investigation of k-fold cross validation because the majority of models use this to validate their estimate of model accuracy. With further help from Ariana’s colleague, Mauro, I was able to gather a ton of data so that I could analyze my results statistically.

Rachael Jaffe

Adam Adli’s ROP399 Journey in Machine Learning and Medical Imaging

costs of its employment, I showed that L2 regularization is a feasible procedure to help prevent over-fitting and improve testing accuracy when developing a machine learning model with limited training data.

machine learning model. I harnessed powerful technologies like Intel AVX2 vectorization instruction set for things like image pre-processing on the CPU and the Nvidia CUDA runtime environment through PyTorch to accelerate tensor operations using multiple GPUs. Overall, the final run of my experiment took about 25 hours to run even with all the high-level optimizations I considered—even on an insane lab machine with an Intel i7-8700 CPU and an Nvidia GeForce GTX Titan X!

Adam

Adli

Summer 2018 ROP: Wenda’s in the house!

X-ray artifacts. And now, looking back, it was one of the best learning experiences I have ever had, through an enormous amount of self-teaching, practicing, troubleshooting, discussing and debating. As with all learning experiences, the process can be long and bewildering, sometimes even tedious; yet rewarding in the end.

office, waiting for him to print out my ROP application and start off the interview. At that point, I just ended my one-year research at a plant lab and was clueless of what I was going to do for the following summer. Coming from a life science background, I went into this interview for a machine learning project in medical imaging knowing that I wasn’t the most competitive candidate nor the most suitable person to do the job. Although I tried presenting myself as someone who had had some experience dealing with statistics by showing Dr. Tyrrell some clumsy work I did for my previous lab, the flaws were immediately noticed by him. I then found myself facing a series of questions which I had no answers to and the interview quickly turned into what I thought to be a disaster for me. I was therefore very shocked when I received an email a week later from Dr. Tyrrell informing me that I had been accepted. I happily went onboard, but joys aside, part of me also had this big uncertainty and doubt that later followed me even to my first few weeks at the lab.

gradually went away. But it was never going to be easy. There were times when

we hit the bottleneck; when our attempts have failed miserably; when we had to give up on a brilliant idea because it didn’t go our ways. But after stumbling through all the challenges and pitfalls, we found ourselves new. I was a bit lost at the beginning of this summer. But over the summer I learned a lot about the very cool and growingly crucial field of machine learning; I grew a newfound appreciation for statistics and methodology; I picked up the programming language python, which I had been wanting to do for years and, most importantly, I did more thinking than I ever would if I were to just follow instructions blindly. And in the end, I believe that science is all about thinking. So for you guys out there reading the blog, if you’re coming to this lab from a totally different background and not entirely sure about the future, don’t be afraid. And I hope you find what you come here looking for, just like I did.

From YSP to Hanging Out at Stanford: Michelle Cheung

My Past and Future at U of T: Helena Lan’s Perspective

Hey everyone, it’s been a while since I posted here. In case you don’t remember me – my name is Helena Lan, and I started in Professor Pascal Tyrrell’s group as a ROP299 student. Fast forward to the present, I have finished my specialist program in pharmacology, and will be graduating with an Honours Bachelor of Science degree later this month! But if you think that I am finally leaving U of T – nope, my journey is not over yet. This August, I will be living my dream of many years as I start my MD training at U of T! As I prepare to begin the next chapter of my life, I wanted to share with you how my involvement in Prof. Tyrrell’s group paved the way for me achieving my goal today.

Afterwards, I continued on as a research assistant, where I explored the need for statistics and research methodology training in the medical imaging department. My early research endeavours showed me that research was not just pipetting; there is a diversity of research that can drive innovations and improve patient care.

ROP299 2017-2018: A Medical Imaging Journey from a Humanities Perspective

My name is Samantha Santoro, and I am completing my second year in the English and Biology majors at the University of Toronto, St. George. A rather unconventional combination, when reviewing past students of Dr. Tyrrell’s lab. I was a 2017-2018 Research Opportunity Program (ROP) student in Dr. Pascal Tyrrell’s lab, and my work chiefly consisted of evaluating the internal vessel wall volumes of carotid arteries in a particular cohort of patients provided by the ongoing prospective CAIN study. My ROP was in the field of Medical Imaging. I am the co-president of the student club known as Watsi, with the main chapter based in San Francisco. I am also a special contributor to the Rare Disease Review, along with volunteering at an amalgamation of charity walks and fundraisers.

My ROP project was a turbulent experience – although that word is typically associated with a negative connotation, I regard my ROP299Y1 as one of the most humbling, interesting, and educative experiences that I have had thus far – most definitely not negative. However, to say everything went smoothly would be discrediting the lessons I learned from when things were not idyllic and smooth. My project, as aforementioned, statistically analyzed data provided by patients part of the CAIN study (an analysis that could not have existed without Dr. Tyrrell’s generous and unwavering support). My study determined that patients who were found to have IPH, or what is known as intraplaque hemorrhage, when I analyzed their MRIs, were also found to have increased vessel wall volume. This conclusion is incredibly significant, as IPH is a surrogate marker for atherosclerosis and could potentially be an indicator for patients at risk of future cerebrovascular events (namely, ischemic stroke). As strokes are currently the number three killer in the U.S and Canada alone, and heart disease number one, having a potential indicator for patients at risk of stroke would greatly benefit clinicians in their practice, as well as patients themselves.

As aforementioned, studies similar to my own are currently underway by the Canadian Atherosclerosis Imaging Network, furthering the important research in this field. The VBIRG (Vascular Biology Imaging Research Group) was the lab in which I primarily worked throughout the course of my ROP, at Sunnybrook Hospital. Moreover, I also worked on systematic reviews and reports outside of the focus of my project, in the fields of medical ethics and AI in the radiology workplace – both of which were opportunities provided to me by Dr. Tyrrell, and both of which were incredibly valuable experiences, allowing for me to broaden my knowledge of certain areas of medicine and science that are developing and expanding.

Although my project was littered with its own respective difficulties – a substantial number of drafts throughout each step of the program (more than I had ever made, even being an English student); a reluctant, but later fulfilling, acquaintanceship with the post-processing software VesselMass; and several late nights learning about the field of statistics – it is in light of these difficulties, and at present having overcome them throughout my ROP, that I remember Dr. Paul Kalanithi’s words in his memoir When Breath Becomes Air: “It occurred to me that my relationship with statistics changed as soon as I became one”. He, too, had studied Biology and English. I may not have played a lead role in the statistics I had been working with, but I can now say that understanding what they meant and how they were formulated has generated a deep respect in me for the field of statistics.

My poster was on display at the 2018 Research Opportunity Undergraduate Fair. Special thanks to Mariam Afshin, my supervisor at Sunnybrook Hospital; Bowen Zhang, for answering each question I had while at Sunnybrook; John, and the rest of the lab team; and Dr. Pascal Tyrrell, for answering my email last February and holding my interview on the same day as my Chemistry exam. Never before had I met such an – in a word – outstanding professor, and I dare say that I will never meet one like him throughout the rest of my academic journey.

Samantha Santoro

Lessons Along the Way

|

| https://betakit.com/startupcfo-explains-the-long-windy-road-to-a-closed-funding-round/ |

review articles – all until I was confident enough to evaluate articles on my own. For me, the key to learning a complex subject was to build on foundational concepts and keep things as clear as possible. As Einstein once said: “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough”.

Fund grant. The lessons for me here? The importance of seeking expert help where appropriate, and that being resourceful can pay off (literally)! Finally, I valued our strong team culture, without which none of this would have been possible.

blogosphere,

Afsaneh Amirabadi & Team

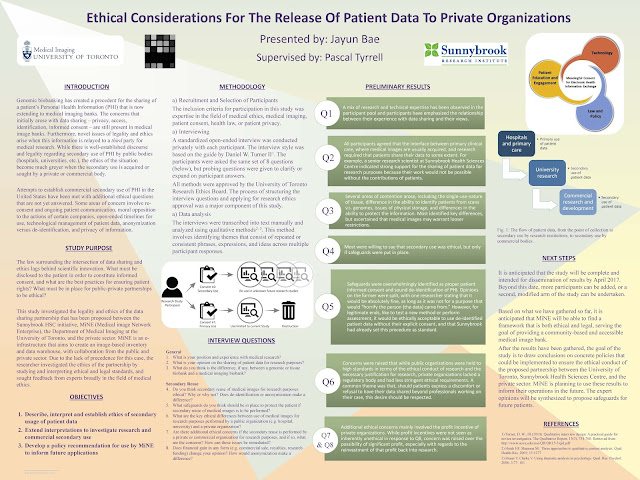

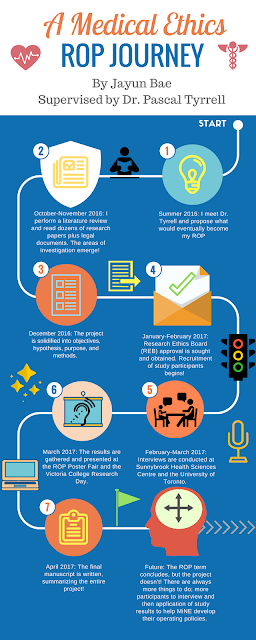

A Medical Ethics ROP Journey with Jayun Bae

|

| Jayun Bae – ROP299Y 2016-17 |

uncovered throughout the project. It quickly became clear that the answers could not be found through an examination of precedence or legal documents, because many of the research actions that would take place (specifically involving private organizations) fell in the grey area between what was legal and what was ethical. For example, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) are two guidelines for organizations to follow when handling patient data – but neither are able to clearly and positively dictate how this partnership should operate.

Dr. Tyrrell for the guidance and mentorship. The project is not yet completed, so I am looking forward to continuing the study beyond the scope of the ROP. Please have a look at my poster from the 2017 ROP Research Day below: