It is never easy to come to an agreement – even amongst friends! The Vultures from Disney’s The Jungle Book (oldie but a goodie) certainly know this. In medical research measuring agreement is also a challenge. In this series of posts I am going to talk about agreement and how it is measured.

Agreement measures the “closeness” between things. It is a broad term that contains both “accuracy” and “precision”. So, let’s say you are shopping for screen protectors for your wonderful new phone. You head to the internet and start going through the gazillion links advertising screen protectors of all sizes and styles. As you just spent your savings on the phone, you do not have much money left over for the screen protector. You decide on a generic brand and order a pack of 10. After an unbearable wait of a week to receive them in the mail you open the pack and find that even though you ordered the screen protector to fit your specific phone they are a little small… except for two that fit perfectly! What? That’s annoying.

So, how close are the screen protectors to being “true” to the expected product? This is agreement. Now, most of them are a little small. This represents poor “accuracy”. This is because there exists a systematic bias. If you took the mean size of these 10 protectors you would find that it deviated from the true expected value – size in this case. Furthermore, you found that two of the 10 protectors actually fit your phone screen rather well. This is great, but this inconsistency between your protectors represents poor “precision”. This time we are interested in the degree of scatter between your measurements – a measure of within sample variation due to random error (see my Dickens post for more info).

Now the concepts of accuracy and precision originated in the physical sciences where direct measurements are possible. Not to be outdone, the social sciences (and then soon to adopt medical sciences!) decided to establish similar concepts – validity and reliability. We will discuss these in a latter post but for now simply remember that the main differences are that a reference is required for validity and that both validity and reliability are most often assessed with scaled indices.

Phew! That was a little confusing. Have a listen to We Just Disagree from Dave Mason to relax.

Next post we will look a little more closely at two special kinds of precision – repeatability and reproducibility.

See you in the blogoshere,

Pascal Tyrrell

It’s All Relevant According to Einstein… or Was It Relative?

One of Einstein‘s many theories is that a light beam always appears to have the same speed, no matter how fast you are moving relative to it. This theory is also one of the foundations of Einstein’s special theory of relativity. So why the Mini Einstein Bobble Head? Because of the Night at the Museum 2 movie, of course! Have a peek at the trailer and come back.

OK, the last letter in our F.I.N.E.R. mnemonic – a convenient way to remember what makes a good research question – is R. We covered E for Ethical last time and today we will go over R for Relevant – not relative (pay attention now!).

So, you are now a junior researcher with a newly minted pocked protector and have decided to step back a minute and assess your research question using F.I.N.E.R. Among the 5 characteristics we have discussed this last one is an important one. Let’s go back to F is for Feasible where we were thinking of a way to survey your friend’s about going camping at the end of the semester to celebrate the start of summer. The results of your survey will provide you with important information. Not only will they influence your decision to have the event or not, but they will also allow for promotion of the event as being “really popular” (important to many participants) and for better planning (important to the organizing committee). The results of the survey are “relevant”.

A Little Respect To Avoid The Blues… Brothers?

In her famous song Respect (have a listen while we chat), Aretha Franklin provides us with a perfect segue to the next letter in our F.I.N.E.R. mnemonic – a convenient way to remember what makes a good research question. We covered N for Novel last time and today we will go over E for Ethical.

Everyone has an idea of what they consider to be “right”. Ethics is a branch of philosophy that focuses on studying what is morally right and wrong in our society. Setting standards to live by that will be in everyone’s best interest. More importantly, ethics also involves the continuous effort of studying our own moral beliefs and our moral conduct, and striving to ensure that we live up to these standards that are reasonable and solidly-based.

Now The Blues Brothers may not have operated with completely ethical methods but you should when you perform research. Wondering what the Blues Brothers have to do with any of this? Watch the trailer and you will see Aretha singing “R-E-S-P-E-C-T”. She wants to be treated “right” just as your subjects will in your study.

But what if you are doing research on your own for fun and are not sure? Ask Mom, she’ll know.

New Gold Dream: Is It that Simple?

What a great album from Simple Minds. Ahhh, the 80’s. Their title track New Gold Dream should get you in the mood for the next letter in our F.I.N.E.R. mnemonic – a convenient way to remember what makes a good research question. We covered I for Interesting last time and today we will go over N for Novel.

No need to reinvent the wheel. You want to save your precious energy and time for answering a question that will move you forward in your area of science.

See you in the blogosphere,

Gwen Stefani Has No Doubt… Do You?

So, in my last post I introduced F.I.N.E.R. as a convenient way to remember what makes a good research question. We covered F for feasible and today we will go over I for Interesting.

What is important when dreaming up a research question is to make sure that you are interested and engaged. This is what will provide you with the energy, drive, and determination to overcome the many hurdles and frustrations that will invariably stand in you way on your path during the research process.

Gwen may have No Doubt about what she is interested in. But do you? How will you gauge how interesting your question is? Easy – talk to people about it. One of the problems new researchers have with their research questions is that they Don’t Speak (great song!) with others during the planning process. Ask as many mentors, experts, family members, friends, colleagues as you can about your question. All that feedback will help you determine whether it is worth your precious time and effort to pursue that research.

Don’t be shy to ask people their opinion and don’t be take it personally if you get negative feedback. It is all part of the process. You can’t expect to have everyone interested but you can certainly try your best to have many.

Try early on in your research career to find a Person of Interest (well maybe not that kind of person) or someone who you value their opinion and are friendly with to act as a sounding board to your ideas before you move on outside the “inner-circle”. You can even repay the favor to them for their research endeavors. Hint: choose wisely…

Try early on in your research career to find a Person of Interest (well maybe not that kind of person) or someone who you value their opinion and are friendly with to act as a sounding board to your ideas before you move on outside the “inner-circle”. You can even repay the favor to them for their research endeavors. Hint: choose wisely…

Next is N…

See you in the blogosphere,

Pascal Tyrrell

What Makes a F.I.N.E.R. Research Question? F is for…

…Fugitive? Well that is certainly how you can feel when out with your friends and knowing you should be home studying for your upcoming stats 101 exam. Not sure how that feels? Watch the trailer from the fantastic movie The Fugitive.

Now that you are well versed in dreaming up research questions and driving everyone around you nuts, I thought I would chat a little about how you can assess whether you have a good one “on the line” or a stinker.

Now that you are well versed in dreaming up research questions and driving everyone around you nuts, I thought I would chat a little about how you can assess whether you have a good one “on the line” or a stinker.

A great mnemonic suggested by Hulley et al is F.I.N.E.R. and suggests that research questions need to be feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant. Today we will talk about the first one.

F is for FEASIBLE. When you are creating a research question you must always ask yourself: “Can I answer this question?”. There are many reasons that may stop you from completing your quest to answer a given question. Maybe not as dramatic as in the Quest for Camelot, but it is important to take note of your limitations:

1- Do you or other members of your team have the know-how or technical expertise to plan, execute, and analyze the study required to answer your question? Maybe you need to brush up on your skills before embarking on your adventure… or phone a friend!

2- Can you afford the time to complete your quest? Do you have the money to pay for it? Gold wins wars not soldiers (Game of Thrones season 1)! Always plan ahead so that your study does not get compromised or cancelled because you don’t have the money or the time to continue (summer student projects often fall pray to this).

3- Do you have access to enough subjects to appropriately power your study? Sample size calculation is a fun and challenging topic and we will address this in later posts. If you want to know how many of your classmates – say 100 – want to go camping over the weekend to celebrate the end of the school year, how many should you ask before you are confident it will be worth your effort to organize the trip? All of them? Some of them? But how many…

4- Are you asking too much at once? Is the scope of your research question too broad? Focus on the most important goals.

Don’t become a “Jack of all trades and master of none“! Aim for a better answer to the main question that you are interested in.

Next post we will move on to I…

See you in the blogosphere,

Pascal Tyrrell

The Order in K-OS and Who’s Dog Is It?

Did you know that Einstein is also known to have contributed significantly to statistical physics? In 1905, he proposed an explanation for the phenomenon called Brownian motion – named after the botanist Robert Brown who first described the process. Essentially, particles suspended in a fluid (liquid or gas) exhibit a random motion (path) resulting from their collision with the quick atoms or molecules in the gas or liquid. This is the K-OS or more appropriately “chaos” of the process. Have a listen to The Dog Is Mine from K-OS to get you ready for some Einstein talk.

The problem with understanding Brownian motion is that the molecules are too light to move the floating particle and molecular collisions occur way more frequently than the observed jiggles.

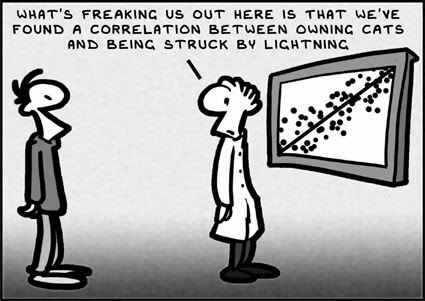

What is the take home message? That much of the order we perceive in the world around us is dependent on an invisible underlying disorder. Words of caution: though random variation can lead to orderly patterns, these patterns are not always meaningful. (See previous posts: Rebel Without a Cause and What Does the Fox Say for some hints on how not to be fooled)

So what is the link between Einstein and The Dog is Mine K-OS song? The dog named Einstein from the Back to the Future movie, of course!

See you in the blogosphere,

Pascal Tyrrell

What Does The Fox Say?

I have often talked about “inferential statistics” in this blog. Don’t remember? Have a quick peek here If Only I Had a Brain and here It’s Cold Out Today – Please Remember to Dress Your Naked P-Value.

Back in the saddle? OK. Lately, I have had the pleasure of addressing young minds (shout out to CAGIS who were AWESOME on Saturday at our Sunnybrook Health Science Center presentation) and I thought I might talk a little about what “inferential” means to statistics.

So What Does The Fox Say? And does Ylvis have the answer? Listen to the song while you read through the rest of the post. We live in a crazy complex world that is largely random and uncertain. This is a good thing as it would be mighty boring to know how everything will turn out in the future. Imagine sitting in the middle of the forest and counting and recording the sounds of ALL animals that pass you – by species! Wow, that’s a lot of data. Now as new research scientists (don’t forget to wear your Pocket Protector before heading out into the woods!) we like ways to describe and make sense of what we observe – we simply want to understand the world better or maybe we are working on a answer to our newly minted Research Question.

Either way you are certainly thinking where does the randomness and uncertainty come into all this? Well, it exists in two places:

1- Most importantly, in the process of what you are interested in studying.

2- But also in how we collect our data (collection and sampling methods).

So you now have an incredible amount of data in your spreadsheet or on little pieces of paper in a shoe box. What now? You have gone from the world around you to data in your hand. You need to somehow capture the essence of all of your data and turn it into something more concise and understandable. You do this by finding “statistical estimators” which means performing appropriate statistical analyses. The results from these analyses will allow you to estimate, predict, or give your “best educated guess” at the answer to your research question.

So by going from the world to your data, and then from your data back to the world is what we call statistical inference.

For example after collecting many days worth of data in the woods, you find that all “furry” creatures make a a kind of barking sound whereas all “feathered” creatures chirp. Excited, you tell your friends that the next time that they are in the woods and they see a furry creature they can expect to hear them bark. However, we do not know that for sure and this is where the uncertainty creeps in.

Ylvis seems to think the fox says:”Ring-ding-ding-ding”. Maybe his data collection and sampling technique was different to yours. This contributes to error and we will talk about this in a later post.

Hopefully you do not feel like you are in the movie “Inception” and… we’ll see you back in the blogoshere soon.

Pascal Tyrrell

Rebel Without a Cause… Or Maybe?

OK, enough with stats. Let’s talk a little about causality. You have been patiently wearing your pocket protector for a couple of months, asking the right questions all the time, and diligently reading this blog to glean as much information as possible to become a research scientist.

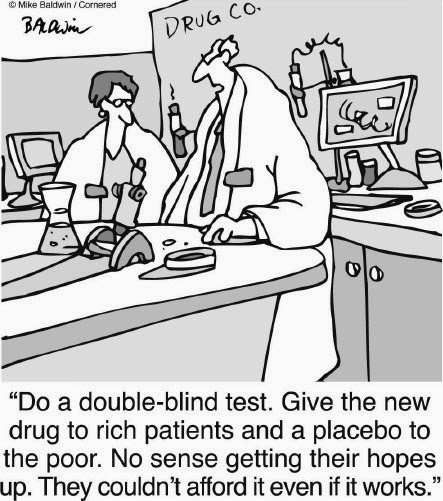

So what now? Do you feel a little like a Rebel Without a Cause? You are asking questions that are interested in describing an association of interest. How about the association between watching horror movies and myocardial infarction (MI). One possibility is that watching horror movies is the cause-effect of an MI. You’re thinking: sure but there must be other explanations. You are right! Actually there can be another 4 rival explanations:

1- By chance alone you observed an association in your data. This is a spurious association.

3- Effect – cause: having an MI is the reason (cause) for watching horror movies – reverse to what you were thinking.

4- Confounding: watching horror movies is associated with a third factor that is the cause of MI. Say eating all those unhealthy snacks during the movie.

And of course don’t forget your initial “gut feeling” cause-effect: watching horror movies is a cause of MI.

Phew! That is a lot to think of. So what is important to remember? When designing your study to answer your question, you must always consider how to avoid spurious associations and concentrate on ruling out real associations that do not represent cause-effect. Especially those due to confounding.

Take a break and watch the Chicken Game from Rebel Without a Cause and then listen to Rebel Music to calm down after the game of chicken. So is playing chicken with cars hurtling towards a cliff associated with death? Possibly. But in watching the clip you see that maybe there is a confounding factor… See it?

Until next time in the blogosphere,

Pascal Tyrrell

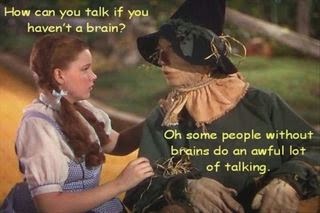

If Only I Had A Brain…

So how was March break? My family and I went to Stowe, Vermont for a little skiing. Awesome. However, the 8 hour drive with 3 kids, our luggage, skis, snowboards, and snacks to get there… maybe not so much. We felt a little like Dorothy in the The Wizard of Oz.

Last time we were talking about p-values and inferential statistics (see Naked p-value if you don’t remember) and I mentioned that I would talk a little more about hypothesis testing. Now Ronald Fisher believed that if you obtained a large p-value when performing a statistical test then you would reject the null hypothesis. So the null hypothesis is always assumed to be true until shown to be false with a statistical test. This helps you determine the probability of seeing an effect as big or bigger than that in your study by chance alone if the null hypothesis were true. This is called significance testing.

Here is an interesting thought: in many (most?) situations the statistical test you perform for the your study is to test the null hypothesis that no difference in effect exists between groups. In our previous example we were interested in whether gals or guys are associated with whether they like the Naked Gun movies or not in the population of blog readers. If no difference truly existed between gals and guys then why perform the study? The null hypothesis that both gals and guys equally like the Naked gun movies is a “straw man” meant to be knocked down by the results of your study. Therefore, you should always maximize the power of your study in order to knock down the straw man and show a difference exists between gals and guys.

Ok. Now that we have worked up a sweat knocking down Scarecrow from the Wizard of Oz, cool down listening to Long December (yes, I am happy spring is around the corner) from the Counting Crows and…

I’ll see you next time in the blogosphere.

Pascal Tyrrell