Rachael Jaffe’s ROP Journey… From the Pool to the Lab!

|

| https://thevarsity.ca/2019/03/10/what-does-a-scientist-look-like/ |

and I was inclined to put my minor to the test! Little did I know that I was about to embark on a machine learning adventure.

wasn’t going to be a part of the lab for 2018-2019 year. If my background in statistics has taught me anything, nothing truly has a 100% probability. And yet, last April I found myself sitting in the department of medical imaging at my first lab meeting.

should add an investigation of k-fold cross validation because the majority of models use this to validate their estimate of model accuracy. With further help from Ariana’s colleague, Mauro, I was able to gather a ton of data so that I could analyze my results statistically.

Rachael Jaffe

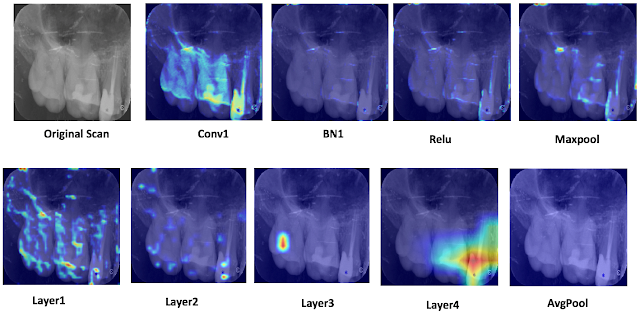

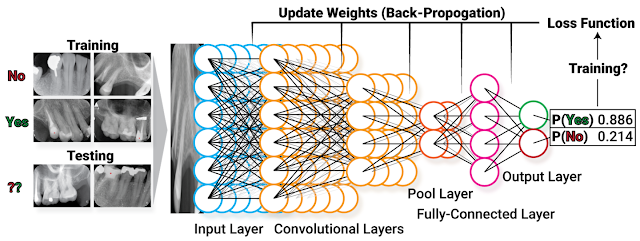

Adam Adli’s ROP399 Journey in Machine Learning and Medical Imaging

costs of its employment, I showed that L2 regularization is a feasible procedure to help prevent over-fitting and improve testing accuracy when developing a machine learning model with limited training data.

machine learning model. I harnessed powerful technologies like Intel AVX2 vectorization instruction set for things like image pre-processing on the CPU and the Nvidia CUDA runtime environment through PyTorch to accelerate tensor operations using multiple GPUs. Overall, the final run of my experiment took about 25 hours to run even with all the high-level optimizations I considered—even on an insane lab machine with an Intel i7-8700 CPU and an Nvidia GeForce GTX Titan X!

Adam

Adli

MiWORD of the day is… Mop-top!

Ahhh, the mop-top! I sigh not because I miss the hairdo but because I miss my hair – all of it. In the mid-60s this hair style was made famous by The Beatles. Don’t know who they are (shame on you!) have a listen here for instruction.

Well the mop-top was made popular because the 4 guys who sported the hairdo were crazy successful musicians from England. Their recording company, Electrical Musical Industries (EMI), was also very happy and successful because of the overwhelming record sales (music was sold to listeners on vinyl records back then).

So, what does any of this have to do with medical imaging? Lots actually. The money generated by record sales enabled the EMI basic science researchers (another division of the company) to work in a prosperous cash-rich environment. One of those researchers was Sir Godfrey Hounsfield, an electrical and computer engineer.

In 1967, he started his work on what would soon become the first CT scanner. By directing x-ray beams through the body at 1 degree angles, with a detector rotating in tandem on the other side, he was able to measure the attenuation of x-rays. These values were then analysed using a mathematical algorithm and a computer to yield a 2-D image of the interior of the body. The production of CT scanners by EMI started in the early 1970s and their monopoly ended by 1975 when companies like DISCO (not even kidding) and GE entered the arena.

Interestingly, in the 1960s Dr Allan Cormack of South Africa had also independently showed similar results to Housfield. In the end, Cormack was cited for his math analysis that led to the CT scan and Housfield for its practical development. They shared the Nobel prize in Physics and Medicine in 1979. Cool.

Now for the fun part (see the rules here), using mop-top in a sentence by the end of the day:

Serious: Who would have thought the success of the mop-top Fab Four would be instrumental in the development of the CT scanner?

Less serious: Hey Bob, I went for my head CT scan today and something weird happened. I went in bald and came out with a mop-top! Is that normal?…

Listen to With a Little Help from My Friends from The Beatles to decompress and…

…I’ll see you in the blogosphere.

Pascal Tyrrell

MiWORD of the day is… Piezoelectric!

Ah, the super villain Livewire. Not sure she was all that much of a challenge for Superman but there you have it: electricity, spandex, and crazy hair. The perfect foe. I wonder if she will make an appearance in the latest Supergirl TV series?

So, today the MiWORD of the day is piezoelectric. Sounds like a fancy name for a downtown pizzaria – but it’s not. Way back before Roentgen discovered x-rays, Pierre and Jacques Curie in 1877 discovered a phenomenon that occurs when crystals are mechanically distorted by external pressure so that an electrical potential develops between the crystal surfaces: the piezoelectric effect. The term was coined by the brothers from the Greek for “pressure-electricity”. So basically, certain crystals (which include quartz, topaz, tourmaline…) can convert electrical to mechanical energy and vice versa.

Why is this important you ask? Well, because this discovery lead to the development of microphones, earphones, and most importantly for us – ultrasound. Based on the physics of sound and not light, ultrasound captures images by manipulating and analyzing sound waves, very high-frequency sound waves as they bounce off surfaces and echo back to the sender. The idea of getting some kind of image from sound waves was first thought of after the sinking of the Titanic in 1912: detecting submerged icebergs with sound reflection.

A little later, in Austria, two brothers Karl and Friedreich Dussik (do you see a trend here?) transmitted sound waves through a patient’s head in 1937. This and then the development of the SONAR (sound navigation and ranging) in WWII was the ground work needed to launch the field of ultrasonography. It would take, however, 20 years after WWII for ultrasonography to become a commercial reality.

Not only is ultrasound one the oldest medical imaging technologies but it is also an important tool for visualizing soft tissue structures in medical diagnosis, follow up of disease processes and pregnancies. Cool.

Now for the fun part (see the rules here), using piezoelectric in a sentence by the end of the day:

Serious: Mom went for her ultrasound today. Told me that I am going to have a little baby sister! She had to wait a while to have her scan because the piezoelectric transducer was on the fritz – again.

Less serious: Hey Bob, do you remember a pizza place on Electric Avenue in Calgary? Piezoelectric something or other? All closed down now. What a shame…

…I’ll see you in the blogosphere.

Pascal Tyrrell

MiWord of the Day Is… CAT scan!

A what scan? I am actually a cat guy myself. Not to say I don’t love dogs but if I had to make a choice…

I just finished reading a fantastic book by David Dosa entitled “Making Rounds With Oscar”. The premise of the book is a story about an extraordinary cat but the subject matter is very serious – dementia and end-of-life care in the elderly. Have a gander.

So what the heck is a cat scan and what does it have to do with medical imaging?

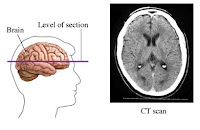

CT scans – also referred to as computerized axial tomography (CAT) – are special X-ray tests that produce cross-sectional images of the body using X-rays and a computer. CT was developed independently by a British engineer named Sir Godfrey Hounsfield and Dr. Alan Cormack and were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in 1979. Yes, more Nobel prize winners…

CT scans – also referred to as computerized axial tomography (CAT) – are special X-ray tests that produce cross-sectional images of the body using X-rays and a computer. CT was developed independently by a British engineer named Sir Godfrey Hounsfield and Dr. Alan Cormack and were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in 1979. Yes, more Nobel prize winners…

In a nutshell, x-ray computed tomography:

– uses data from several X-ray images of structures inside the body and converts them into 3D pictures – especially useful for soft tissues.

– emits a series of narrow beams through the human body, producing more detail than standard single beam X-rays.

– is able to distinguish tissues inside a solid organ. A CT scan is able to illustrate organ tear and organ injury quickly and so is often used for accident victims.

– is analyzed by radiologists.

Unfortunately, unlike MRI scans, a CT scan uses X-rays and therefore are a source of ionizing radiation.

Now for the fun part (see the rules here), using CAT Scan in a sentence by the end of the day:

Serious: Hey Bob, did you know that the recorded image of a CAT Scan is called a tomogram?

Less serious: My GP suggested that howling at the moon at night is not normal behavior and he wants to send me for a CAT scan. What? No way, I’m allergic to cats…

OK, listen to Cat Stevens to decompress and I’ll see you in the blogosphere…

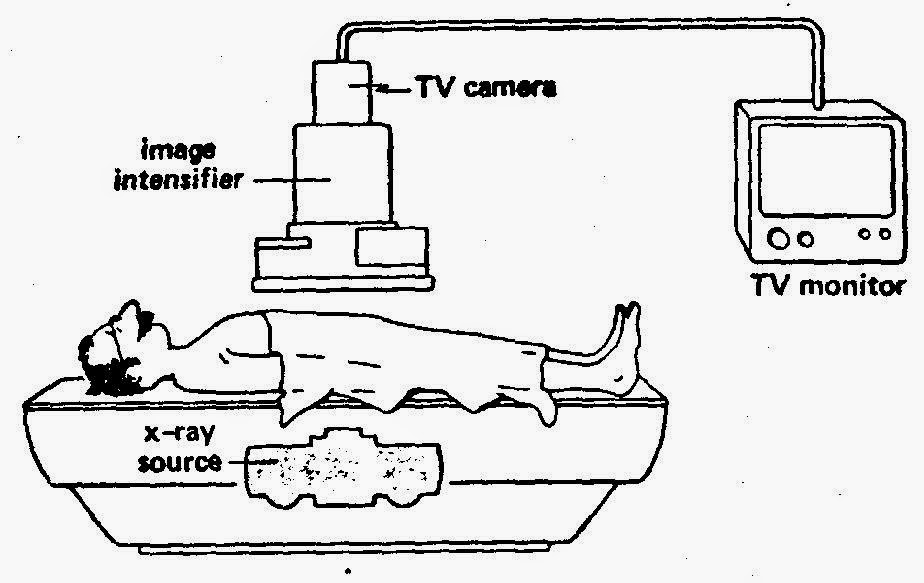

MiWord of the Day Is… Cinemaradiology!

Yes, it is Halloween today and my kids could barely contain themselves getting ready for school. I suspect today will not be very productive as they count down the minutes before heading out to terrorize my neighbors.

Anyway, how about this for a scary thought: cinemaradiology! In the late 1800’s John MacIntyre at the Gasgow Royal Infirmary experimented with producing X-ray motion pictures. What!!!? He tried exposing film by passing it between the screen of the fluoroscope and the x-ray tube and by simply filming the fluoroscopic screen. This latter method was very difficult because, as all of you budding radiologists know, the images viewed on the fluoroscope screen were dim and of poor resolution at the time.

For years researchers worked on perfecting cinemaradiology. However, during those early years of discovery they lost interest when they realized that sharper images were possible when BOTH patients and investigators were exposed together AND that excessive radiation was a bad thing – duh!

It would only be many many years later that fluoroscope screen technology would be improved to allow for brighter and higher resolution images (and without frying the patient and everyone around!).

To my knowledge, no actors from the cinemaradiology era ever became successful stars in Hollywood…

No need to use the MiWord of the day in a sentence today (see rules here) as I realize you are busy getting ready for Halloween and need a break!

Decompress listening to the classic song Thriller by the King of Pop Michael Jackson and I’ll see you in the blogosphere…

Pascal Tyrrell

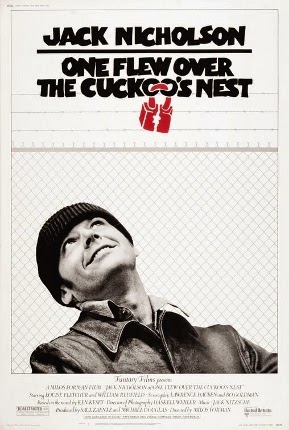

MiWord of the Day Is… Cuckoo!

One of my favorite more serious films is One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. What does Jack Nicholson’s portrayal of a bad guy hoping for easy served time in a mental institution have to do with medical imaging? Well it all starts with the lobotomy. Not to spoil the story, suffice it to say that the movie broaches the topic of lobotomies and how ridiculous they were. Lobotomy was a form of neurosurgery that involved damaging the prefrontal cortex in order to “calm” certain mentally ill patients. Needless to say the procedure was controversial from the beginning (1935 to the early 1970’s) but the author of the discovery, Egas Moniz, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1949. Maybe not the most sound of decisions by the committee. However, for the time, it was considered progress in a very challenging area of medicine – mental illness.

OK, medical imaging? Well as it turns out Moniz (do not confuse with St-Moriz, ahhh skiing…) is also known for developing cerebral angiography – a technique allowing the visualization of blood vessels in and around the brain.

Moniz was interested in finding a non-toxic substance that would be eliminated from the body, but would not be diluted by the flow of blood before the x-ray could be taken. Another requirement is that the substance could not cause an emboli or clot as this would be a bad thing. Moniz played with salts of iodine and bromine and settled on iodine because of its greater radiographic density. And voila, birth of iodinated radiocontrast agents still in use today. Cool.

Supposedly it took him 9 patients to perfect his angiogram technique. Don’t ask about the first 8…

Moral of the story is: lobotomy bad and cerebral angiography good.

Now for the fun part (see the rules here), using Cuckoo in a sentence by the end of the day:

Less serious: Someone won a Nobel Prize for developing the lobotomy? Are you cuckoo?

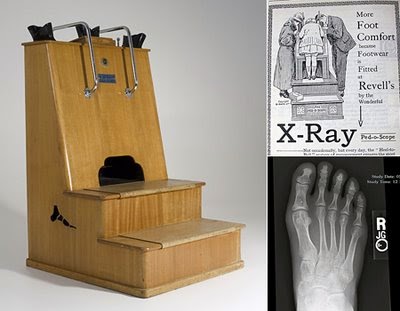

MiWord of the Day Is… Fluoroscope!

Fluoroscopes have come a long way over the years and are still used today in areas such as orthopedic surgery, gastrointestinal investigations, and angiography but, of course, the dose of x-rays a patient receives is minimized and closely monitored. Have a look at this machine from Siemen’s. “Beam me up Scotty!”.

Fluoroscopes have come a long way over the years and are still used today in areas such as orthopedic surgery, gastrointestinal investigations, and angiography but, of course, the dose of x-rays a patient receives is minimized and closely monitored. Have a look at this machine from Siemen’s. “Beam me up Scotty!”.  Due to the enormous supply of portable x-ray machines at the time following the end of the war, Dr Jacob Lowe introduced the idea of using a modified portable x-ray machine in the shoe retail industry. Voila, fried feet fricassee for the next 50 years!

Due to the enormous supply of portable x-ray machines at the time following the end of the war, Dr Jacob Lowe introduced the idea of using a modified portable x-ray machine in the shoe retail industry. Voila, fried feet fricassee for the next 50 years!Now If were to be interested in using a fluoroscope to look at my feet I may be inclined to use a suit like this gentleman below is sporting…

|

| WW I x-ray protection suit |

Now for the fun part, using Fluoroscope in a sentence by the end of the day:

Serious: Bob, did you know that the foot-o-scope was a modified fluoroscope used to view ones feet when fitting new shoes which delivered on average 13 Roentgens for every 20 second exposure?

Less serious: I heard grampa grumbling he can never find shoes that fit right anymore since they banned fluoroscopes in shoe stores. What is a fluoroscope mommy?

Listen to High Heels to decompress and I’ll see you in the blogosphere.

Pascal Tyrrell

MiWord of the Day Is… Radio!

Easy one today! I thought I would give everyone a break as you have all been working very hard on the MiWord of the day in the past weeks.

So, what does radio have to do with medical imaging? What a great question! The origin of the root word “Radio” is radiant energy. The radio you immediately think of is the one that is attached to your ear most of the time and has a DJ who selects music to play for your entertainment – along with ads to pay for the station’s bills! The use of “radio” to describe this form of wireless communication comes from the word radiotelegraphy.

How about if we were simply interested in a medical picture produced by radiant energy? Well you would end up with a radiograph AKA an x-ray! We talked about that word here. Do you see the trend? How about a picture produced by radiant energy in the visible light range of the electromagnetic spectrum? A photograph. Cool.

OK now suppose you are an MD working in the emergency department and someone presents with a lung disorder. What do you do? Generally, you order a chest radiograph. As you zap your patient with x-rays you expect that most of them will pass through the chest area – that is mostly filled with air – unchecked and will proceed to expose the film (or trigger the detector) resulting in a dark area. However, if the lungs become filled with abnormal substances more of the x-rays are blocked and result in a lighter (whiter) radiograph. What would you be looking for?

1- Pus – a combination of bacteria and white blood cells as seen with pneumonia.

2- Edema – fluid that leaks into the lungs as seen with heart failure.

3- Hemorrhage – bleeding into the lung cavity as seen with trauma.

4- a solid mass – as seen in lung cancer.

Today, we have to use “Radio” in a sentence (see rules here). Easy! Here are two examples to help you along:

Serious: Bob, you will need to remove your radio from your person before entering the MRI. No metal objects are permissible in the room.

Less serious: I went for a radiograph today and all they did was have me stand in a room by myself and that was it! What a relief. I thought for a moment I was scheduled for a radio-graft…!

Have a listen to my favorite Radiohead to decompress and…

… I’ll see you in the blogosphere,

Pascal Tyrrell